Intimidated By CSS? The Definitive Guide To Make Your Fear Disappear

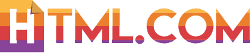

CSS is the language that defines the presentation of a web page. It is used to add color, background images, and textures, and to arrange elements on the page. However, CSS does a lot more than just paint a pretty picture. It is also used to enhance the usability of a website. The image below shows the front page of YouTube. On the left, is a regular rendering of the page, and on the right you can see how it looks without CSS.

Not only is the image on the right less interesting, but it is also a lot harder to use.

In this short guide, we’ll introduce CSS, demonstrate CSS syntax, explain how CSS works, show you how to add CSS markup to an HTML document, and point you toward great resources from around the web where you can learn more about CSS.

Contents

What is CSS?

CSS stands for Cascading Style Sheets and it is the language used to style the visual presentation of web pages. CSS is the language that tells web browsers how to render the different parts of a web page.

Every item or element on a web page is part of a document written in a markup language. In most cases, HTML is the markup language, but there are other languages in use such as XML. Throughout this guide we will use HTML to demonstrate CSS in action, just keep in mind that the same principles and techniques apply if you’re working with XML or a different markup language.

How is CSS Different From HTML?

The first thing to understand when approaching the topic of CSS is when to use a styling language like CSS and when to use a markup language such as HTML.

- All critical website content should be added to the website using a markup language such as HTML.

- Presentation of the website content should be defined by a styling language such as CSS.

Blog posts, page headings, video, audio, and pictures that are not part of the web page presentation should all be added to the web page with HTML. Background images and colors, borders, font size, typography, and the position of items on a web page should all be defined by CSS.

It’s important to make this distinction because failing to use the right language can make it difficult to make changes to the website in the future and create accessibility and usability issues for website visitors using a text-only browser or screen reader.

CSS Syntax

CSS syntax includes selectors, properties, values, declarations, declaration blocks, rulesets, at-rules, and statements.

- A selector is a code snippet used to identify the web page element or elements that are to be affected by the styles.

- A property is the aspect of the element that is to be affected. For example, color, padding, margin, and background are some of the most commonly used CSS properties.

- A value is used to define a property. For example, the property color might be given the value of red like this:

color: red;. - The combination of a property and a value is called a declaration.

- In many cases, multiple declarations are applied to a single selector. A declaration block is the term used to refer to all of the declarations applied to a single selector.

- A single selector and the declaration block that follows it in combination are referred to as a ruleset.

- At-rules are similar to rulesets but begin with the @ sign rather than with a selector. The most common at-rule is the

@mediarule which is often used to create a block of CSS rules that are applied based on the size of the device viewing the web page. - Both rulesets and at-rules are CSS statements.

An Example of CSS Syntax

Let’s use a block of CSS to clarify what each of these items is.

h1 {

color: red;

font-size: 3em;

text-decoration: underline;

}

In this example, h1 is the selector. The selector is followed by a declaration block that includes three declarations. Each declaration is separated from the next by a semicolon. The tabs and line breaks are optional but used by most developers to make the CSS code more human-readable.

By using h1 as the selector, we are saying that every level 1 heading on the web page should follow the declarations contained in this ruleset.

The ruleset contains three declarations:

color:red;font-size: 3em;text-decoration: underline;

color, font-size, and text-decoration are all properties. There are literally hundreds of CSS properties you can use, but only a few dozen are commonly used.

We applied the values red, 3em, and underline to the properties we used. Each CSS property is defined to accept values formatted in a specific way.

For the color property we can either use a color keyword or a color formula in Hex, RGB, or HSL format. In this case, we used the color keyword red. There are a few dozen color keywords available in CSS3, but millions of colors can be accessed with the other color models.

We applied the value of 3em to the property font-size. There are a wide range of size units we could have used including pixels, percentages, and more.

Finally, we added the value underline to the property text-decoration. We could have also used overline or line-through as values for text-decoration. In addition, CSS3 allows for the use of the line-styles solid, double, dotted, dashed, and wavy was well the specification of text-decoration colors. We could have applied all three values at once by using a declaration like this:

text-decoration: blue double underline;

That rule would cause the h1 in our initial example to be underlined with a blue double line. The text itself would remain red as defined in our color property.

Preparing HTML Markup for Styling

CSS should be used to add content to a web page. That task is best handled by markup languages such as HTML and XML. Instead, CSS is used to pick items that already exist on a web page and to define how each item should appear.

In order to make it as easy as possible to select items on a web page, identifiers should be added to elements on the webpage. These identifiers, often called hooks in the context of CSS, make it easier to identify the items that should be affected by the CSS rules.

Classes and IDs are used as hooks for CSS styles. While the way CSS renders is not affected by the use of classes and hooks, they give developers the ability to pinpoint HTML elements that they wish to style.

Classes and IDs aren’t interchangeable. It’s important to know when to use each.

When to Use Classes

Use classes when there are multiple elements on a single web page that need to be styled. For example, let’s say that you want links in the page header and footer to be styled in a consistent manner, but not the same way as the links in the body of the page. To pinpoint those links you could add a class to each of those links or the container holding the links. Then, you could specify the styles using the class and be sure that they would only be applied to the links with that class attribute.

When to Use IDs

Use IDs for elements that only appear once on a web page. For example, if you’re using an HTML unordered list for your site navigation, you could use an ID such as nav to create a unique hook for that list.

Here’s an example of the HTML and CSS code for a simple navigation bar for a basic e-commerce site.

<style>

#nav {

background: lightgray;

overflow: auto;

}

#nav li {

float: left;

padding: 10px;

}

#nav li:hover {

background: gray;

}

</style>

<ul id="nav">

<li><a href="">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="">Shop</a></li>

<li><a href="">About Us</a></li>

<li><a href="">Contact Us</a></li>

</ul>

That code would produce a horizontal navigation menu with a light gray background beginning from the left-hand side of the page. Each navigation item will have 10 pixels of spacing on all sides and the background of each item will become darker when you allow your mouse to hover over it.

Any additional lists on the same web page would not be affected by that code.

#example-nav {

background: lightgray;

overflow: auto;

}

#example-nav li {

float: left;

padding: 10px;

}

#example-nav li:hover {

background: gray;

}

When Not to Use Hooks

You don’t have to add a class or ID to an HTML element in order to style it with CSS. If you know you want to style every instance of a specific element on a web page you can use the element tag itself.

For example, let’s say that you want to create consistent heading styles. Rather than adding a class or ID to each heading it would be much easier to simply style all heading elements by using the heading tag.

<style>

ul {

list-style-type: upper-roman;

margin-left: 50px;

}

p {

color: darkblue

}

</style>

<p>Some paragraph text here. Two short sentences.</p>

<ul>

<li>A quick list</li>

<li>Just two items</li>

</ul>

<p>Additional paragraph text here. This time let's go for three sentences. Like this.</p>

That code would render like this.

.code_sample ul {

list-style-type: upper-roman;

margin-left: 50px;

}

.code_sample p {

color: darkblue

}

Some paragraph text here. Two short sentences.

- A quick list

- Just two items

Additional paragraph text here. This time let’s go for three sentences. Like this.

- Another list

- Still just two items

In this case, even though we only wrote the style rules for ul and p elements once each, multiple items were affected. Using element selectors is a great way to create an attractive, readable, and consistent website experience by creating consistent styling of headings, lists, and paragraph text on every page of the website.

Best Practices for Preparing Your Markup for Styling

Now that you know how classes, IDs, and element tags can be used as hooks for CSS rulesets, how can you best implement this knowledge to write markup that makes it easy to poinpoint specific elements?

- Apply classes liberally and consistently. Use classes for items that should be aligned in one direction or the other, and for any elements that appear repeatedly on a single web page.

- Apply IDs to items that appear only once on a web page. For example, use an ID on the

divthat contains your web page content, on theulthat that contains the navigation menu, and on thedivthat contains your web page header.

Ways of Linking CSS Rules to an HTML Document

There are three ways of adding CSS rules to a web page:

- Inline styles

- Internal stylesheets

- External stylesheets

In the vast majority of cases, external stylesheets should be used. However, there are instances where inline styles or internal stylesheets may be used.

Inline Styles

Inline styles are applied to specific HTML elements. The HTML attribute style is used to define rules that only apply to that specific element. Here’s a look at the syntax for writing inline styles.

<h1 style="color:red; padding:10px; text-decoration:underline;">Example Heading</h1>

That code would cause just that heading to render with red underlined text and 10 pixels of padding on all sides. There are very few instances where inline styles should be used. In nearly all cases they should be avoided and the styles added to a stylesheet.

Internal Stylesheets

The earlier examples in this tutorial make use of internal stylesheets. An internal stylesheet is a block of CSS added to an HTML document head element. The style element is used between the opening and closing head tags, and all CSS declarations are added between the style tags.

We can duplicate the inline styles from the code above in an internal stylesheet using this syntax.

<head>

<style>

h1 {

color: red;

padding: 10px;

text-decoration: underline;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Example Heading</h1>

</body>

That code would produce the same results as the inline styles. However, the benefit to using internal stylesheets rather than inline styles is that all h1 elements on the page will be affected by the styles.

External Stylesheets

External stylesheets are documents containing nothing other than CSS statements. The rules defined in the document are linked to one or more HTML documents by using the link tag within the head element of the HTML document.

To use an external stylesheet, first create the CSS document.

/*************************************************

Save with a name ending in .css such as styles.css

*************************************************/

h1 {

color: red;

padding: 10px;

text-decoration: underline;

}

Now that we have an external stylesheet with some styles, we can link it to an HTML document using the link element.

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="styles.css">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Example Heading</h1>

</body>

When this HTML document is loaded the link tag will cause the styles in the file styles.css to be loaded into the web page. As a result, all level 1 heading elements will appear with red text, underlined, and with 10 pixels of padding applied to every side.

When to Use Each Method

In nearly all cases external stylesheets are the proper way to style web pages. The primary benefit to using external stylesheets is that they can be linked to any number of HTML documents. As a result, a single external stylesheet can be used to define the presentation of an entire website.

Internal stylesheets may be used when designing a simple one-page website. If the website will never grow beyond that single initial page using an internal stylesheet is acceptable.

Inline styles are acceptable to use in two instances:

- When writing CSS rules that will only be applied to a single element on a single web page.

- When applied by a WYSIWYG editor such as the tinyMCE editor integrated into a content management system such as WordPress.

In all other cases, inline styles should be avoided in favor of external stylesheets.

How CSS Works

When writing CSS, there are many times that rules are written that conflict with each other. For example, when styling headers, all of the following rules may apply to an h1 element.

- An element-level rule creating consistent

h1rendering across all pages of the website. - A class-level rule defining the rendering of

h1elements occurring in specific locations – such as the titles of blog posts. - An id-level element defining the rendering of an

h1element used in just one place on a one or more web pages – such as the website name.

How can a developer write rules that are general enough to cover every h1 yet specific enough to define styles that should only appear on specific instances of a given element?

CSS styles follow two rules that you need to understand to write effective CSS. Understanding these rules will help you write CSS that is broad when you need it to be, yet highly-specific when you need it to be.

The two rules that govern how CSS behaves are inheritance and specificity.

Cascading Inheritance

Why are CSS styles called cascading? When multiple rules are written that conflict with each other, the last rule written will be implemented. In this way, styles cascade downward and the last rule written is applied.

Let’s look at an example. Let’s write two CSS rules in an internal stylesheet that directly contradict each other.

<head>

<style>

p {color: red;}

p {color: blue;}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<p>What color will the text of this paragraph be?</p>

</body>

The browser will cascade through the styles and apply the last style encountered, overruling all previous styles. As a result, the heading is blue.

.code_sample_p {color: red;}

.code_sample_p {color: blue;}

What color will the text of this paragraph be?

This same cascading effect comes into play when using external stylesheets. It’s common for multiple external stylsheets to be used. When this happens, the style sheets are loaded in the order they appear in the HTML document head element. Where conflicts between stylesheet rules occur, the CSS rules contained in each stylesheet will overrule those contained in previously loaded stylesheets. Take the following code for example:

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="styles_1.css">

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="styles_2.css">

</head>

The rules in styles_2.css will be applied if there are conflicts between the styles contained in these two stylesheets.

Inheritance of styles is another example of the cascading behavior of CSS styles.

When you define a style for a parent element the child elements receive the same styling. For example, if we apply color styling to an unordered list, the child list items will display the same styles.

<head>

<style>

ul {color: red;}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<ul>

<li>Item 1</li>

<li>Item 2</li>

</ul>

</body>

Here’s how that code would render.

- Item 1

- Item 2

Not every property passes from a parent to its child elements. Browsers deem certain properties as non-inherited properties. Margins are one example of a property that isn’t passed down from a parent to a child element.

Specificity

The second rule that determines which rules are applied to each HTML element is the rule of specificity.

CSS rules with more specific selectors will overrule CSS rules with less specific selectors regardless of which occurs first. As we discussed, the three most common selectors are element tags, classes, and ids.

- The least specific type of selector is the element level selector.

- When a class is used as a selector it will overrule CSS rules written with the element tag as the selector.

- When an ID is used as a selector it will overrule the CSS rules written with element or class selectors.

Another factor that influences specificity is the location where the CSS styles are written. Styles written inline with the style attribute overrule styles written in an internal or external stylesheet.

Another way to increase the specificity of a selector is to use a series of elements, classes, and IDs to pinpoint the element you want to address. For example, if you want to pinpoint unordered list items on a list with the class “example-list” contained with a div with the id “example-div” you could use the following selector to create a selector with a high level of specificity.

div#example-div > ul.example-list > li {styles here}

While this is one way to create a very specific selector, it is recommended to limit the use of these sorts of selectors since they do take more time to process than simpler selectors.

Once you understand how inheritance and specificity work you will be able to pinpoint elements on a web page with a high degree of accuracy.

What Can CSS Do?

A better question might be: “What can’t CSS do?”

CSS can be used to turn an HTML document into a professional, polished design. Here are a few of the things you can accomplish wish CSS:

- Create a flexible grid for designing fully responsive websites that render beautifully on any device.

- Style everything from typography, to tables, to forms, and more.

- Position elements on a web page relative to one another using properties such as

float,position,overflow,flex, andbox-sizing. - Add background images to any element.

- Create shapes, interactions, and animations.

These concepts and techniques go beyond the scope of this introductory guide, but the following resources will help you tackle these more advanced topics.

The Box Model

If you plan to use CSS to build web page layouts, one of the first topics to master is the box model. The box model is a way of visualizing and understanding how each item on a web page is a combination of content, padding, border, and margin.

.png)

Understanding how these four pieces fit together is a fundamental concept that must be mastered prior to moving on to other CSS layout topics.

Two great places to learn about the box model include:

- An explanation of the box model from the World Wide Web Consortium.

- An introduction to the CSS box model from the Mozilla Developer Network.

Creating Layouts

There are a number of techniques and strategies used to create layouts with CSS, and understanding the box model is a prerequisite to every strategy. With the box model mastered you’ll be ready to learn how to manipulate boxes of content on a web page.

The Mozilla Developer Network offers a good introduction to CSS layouts. This short read covers the basic concepts behind CSS layouts, and quickly introduces properties such as text-align, float, and position.

A much more extensive an in-depth guide to CSS layouts is available from the W3C: The CSS layout model. This document is a resource for professional developers, so if you’re new to CSS take your time as you review it. This isn’t a quick read. However, everything you need to know about creating CSS layouts is contained in this document.

Grid layouts have been the go-to strategy for designing responsive layouts for several years. CSS grids have been created from scratch for years and there are many different grid-generating websites and development frameworks on the market. However, within a few years, support for grid layouts will be part of the CSS3 specification. You can learn a lot about grids by reading up on the topic at the W3C website. For a lighter and shorter introduction to grid layouts, take a look at this article from Mozilla.

Within a few years, CSS3 Flexible Box, or flexbox, is expected to become the dominant model for designing website layouts. The flexbox specification is not yet entirely complete and finalized, and support for flexbox is not consistent between browsers. However, every budding CSS developer needs to be familiar with flexbox and prepared to implement it in near future. The Mozilla Developer Network is one of the best places to get up to speed on flexbox.

Web Fonts & Typography

There’s a lot that can be done to add personality and improve the readability of the content on a website. Learn more about selecting fonts and typography for the web in our guide to Fonts & Web Typography.

Create a Consistent Cross-Browser Experience

Every browser interprets the HTML specification a little differently. As a result, when identical code is rendered in two different browsers, there are often minor differences in the way the code is rendered.

Take this short bit of code for instance.

<h1>Heading 1</h1>

<p>A short paragraph of text. Just four sentences. Most of the sentences are quite short. Especially this one.</p>

<h2>Heading 2</h2>

<ul>

<li>Just a short list</li>

<li>Three items on this list</li>

<li>We'll make it an unordered list</li>

</ul>

<h3>Heading 3</h3>

<p>One final short paragraph of text. Just four sentences. Most of the sentences are quite short. Especially this one.</p>

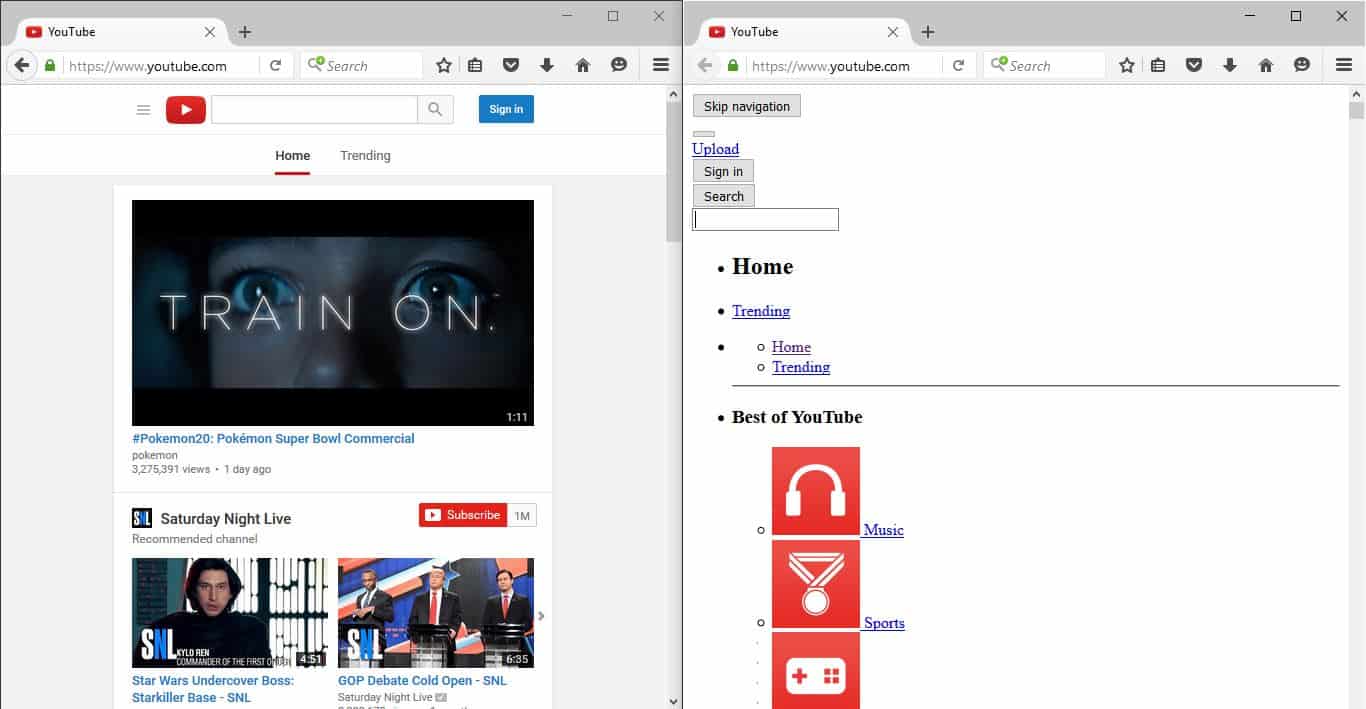

If we render that code in two different browsers we will see subtle differences. Here’s how Mozilla Firebox and Microsoft Edge render that code.

Can you see the subtle differences? Firefox, on the left, adds just a little more margin around each heading element. In addition, the bullet points are a little smaller when rendered in Edge. While these differences are not consequential there are instances where these minor variations between browsers can create problems.

CSS can be used to smooth out these cross-browser compatibility issues. One popular way to do this is to implement a boilerplate CSS document called normalize.css. This freely-available CSS file can be linked to any HTML document to help minimize cross-browser rendering differences.

The easiest way to include normalize.css in your design work is to link to the copy hosted by Google. To do so, just drop this line of code into the head element of an HTML document.

<link rel="stylesheet" src="//normalize-css.googlecode.com/svn/trunk/normalize.css" />